The new professor

I began working as an associate professor at Meio University in the spring of 2014, after I had been living in Okinawa, Japan for a year and a half. The job was a unique opportunity for me to continue that work that I had been doing teaching English at a local business college, where the majority of my students were studying to work in the tourism industry. Meio is a private university with a thriving study abroad program as well as a small population of international students. During my time at the university, I worked with students from all over Japan as well as students from Brazil, China, Hong Kong, the Philippines, and Thailand.

Although I didn’t realize it at the time, my work as an ELL instructor was continuing to serve as a crash course in how to teach clearly according to UX Writing principles. What I mean by this is that I had to change how I spoke to and taught in English in order to be better understood. My students came from a variety of English-learning backgrounds, and although some lesson customization was necessary, it mainly meant that I relied on and had success with a more one-size-fits-all approach. I would:

Give simple imperative instructions

Avoid adjectives that didn’t communicate purpose

Ask direct questions

The invitation to work at Meio represented the further opportunity to create new curriculum in several courses for written and spoken English for first and second-year students, and particularly the opportunity to drive innovation in the seminar ‘Intercultural Communication Theory.’ I had been given the assigned textbook that had been used in this course for the last ten years, and found it dated and not really pushing the students to broaden their cultural understanding. Although I used some of the themes that delineated lessons in the textbook, I developed my own curriculum for the themes:

Identity

Values

Culture in Language

Body Language

Individualism

I was excited by the chance to continue to educate and prioritize spoken and written communication, which I had found to be more limited in the Japanese education system than in the French or even the American. Although Japanese students begin typically learning English by their middle school years at the latest, there is a large emphasis put on listening and answering questions to English dialogues, but, from what I had seen, there wasn’t as much being done to promote having conversations, such that during the first few classes whenever I had new students, a number were visibly shocked that I would begin each class with, “Good morning! How are you?” and expected a response from the students. It was, at least, a solid benchmark to begin from.

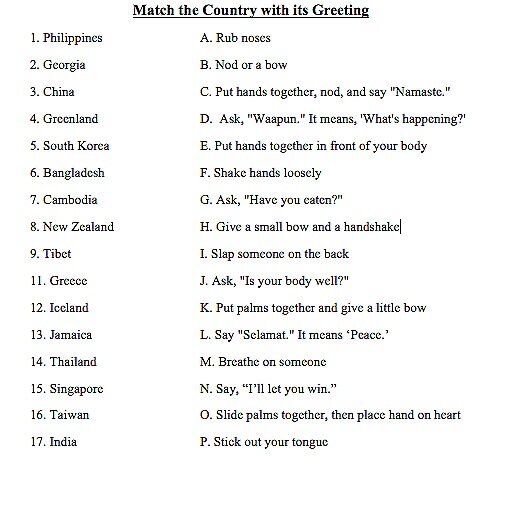

Class icebreaker: Greetings around the world

I decided to begin my first class with a look at how greetings are done around the world. I broke the class into groups of 4-5 students, and passed out this worksheet:

It was clear that many of my new students had never done anything like this before- comparing and contrasting the greeting style that was familiar to them with what was customary in other countries. I was encouraged to notice that the students worked together in their new groups, sometimes demonstrating a greeting rather than looking up an unknown word in a dictionary.

At the end of the warm-up, I wrote a few questions for my students to consider on the board, giving them a few minutes to think about their answers:

How do you greet people? What is different or the same about it to the above greetings?

Which of these greetings would be a challenge for you?

Which of these greetings is fun?

When it came time to share, I was not surprised that there was a certain amount of resistance to being the first to answer my questions. So, I demonstrated, shaking hands with myself, then stating that a handshake can also be a greeting in South Korea, while it is different from putting both hands together and bowing, as is done in Thailand. A few students then offered their own answered, and we moved on to speaking about which of the greetings would challenging given culture or personal preference. A few of my favorite comments:

“I would not want someone I did not know to breathe on me.”

“To stick out my tongue seems rude.”

“I don’t know if I want to say how my body is.”

It was a good sign that the students were smiling, especially as we moved to talk about fun. The students were more comfortable talking about this than a challenge, and answered more freely.

“I think to wish peace is a good thing.”

“Rubbing noses is cute! I would do that with a close friend.”

“I am often hungry, so I think it’s nice to share food.”

Last but not least, I gave my students the opportunity to introduce themselves to the class and gave them no additional instructions. A handful of students took me up on my offer, providing their names, hometowns, and usually one detail, such as a pet or a favorite food. I felt that we were off to a good start.

culture shock

After I been teaching the class for a few weeks, I decided to experiment with a lesson about encountering the uncomfortable. When people travel, they see things that are uncomfortable to them, but are normal to the culture they exist in. From my own experience, I could remember being chastised for wearing a sweater that had inadvertently risen up to reveal my hip before entering the outer courtyard of a mosque, and feeling humiliated for not noticing. I could also remember feeling ignorant after draining the bathwater that was meant to be shared by a family when I went to visit a Japanese acquaintance and his wife. Although they weren’t comfortable experiences for me, I learned from them.

I had been conducting my classes in a very open manner, beginning with a small introduction to the topic, and then allowing ample time for a class activity that gave the students a lot of opportunity to ask questions about new material. As my students were generally reserved, I was not sure what to expect with teaching about cultural practices that might be seen as, at best, impolite. However, as many of my students were likely to study abroad, I saw the lesson as practice for future cultural encounters.

I had the students divide into groups, and I gave each group a photograph. The two photographs that resulted in the most gasps on both occasions that I taught this lesson were that of the dog meat market and that of the open-air toilet. In the first round, several students showed their photos to other groups, as if comparing notes.

I wrote a few questions on the board for my students to think and write notes about within their groups:

Is this photo shocking? If ‘yes’, why?

Have you ever seen this before?

Where do you think this picture is?

I continued the exercise until all of the groups had seen all of the pictures. I then had each group determine which photo they found to be the most shocking. Although it was plain that my students would never eat a fried tarantula, the dog meat market was far more shocking, and none of my students had seen one in person.

“I could never eat a dog.”

“It is so sad to see them like that.”

“It does not seem natural.”

“I did not know that people ate dogs.”

A photo that also generated a lot of commentary was of the starving children, and I ended up feeling like Kevin Carter, the photographer who captured the starving child in the Sudan with a vulture at her back.

“I can’t look at this very much.”

“They have so much pain.”

“I don’t know how this happens.”

I had to re-evaluate my own sense of bias, as in such a peaceful country, I would have thought the soldier casually buying candy with an automatic rifle would have led to more of a reaction. I had not considered that given the popularity of video games that seeing a gun in a picture, no matter the setting, didn’t seem to impress my students as unusual. My students filled me with optimism when they further observed, "“There’s nothing strange about women who are soldiers.”

As about half of the class had traveled within Asia, they were least shocked by the family of seven who were traveling on a moped, although the consensus was that it was “dangerous.”

Although my students observed that the women in burkhas "“looked like ghosts” they were not shocked given that they had seen pictures of women in burkhas on the news.

In the end, the lesson I was hoping to impart to my students was that, having seen things for ourselves nearly always makes them less shocking.

That being said, I’m still quite sure I would do well at a dog meat market.

Cultural Exploration: Dance

I wanted my students to begin thinking about the ways in which, at the risk of sounding too earthy-crunchy, we are all similar across global cultures. I had done this through lessons at the business college such as

Inter-language idiom explorations

How many cultures have a thanksgiving holiday, including Israel, South Korea, Germany, Liberia, The Netherlands, China, and Thailand

A game comparing what makes countries unique

But I thought it might be interesting to teach a lesson that was based on how movement and the use of music could spread across culture, and, as a lifelong lover of dance, I thought this would be an interesting basis for comparison.

I was hoping that my students would walk away from the lesson thinking about how dance was a useful lesson in how a cultural practice can both speak to the culture it arises from as well as borrow from other variations and still remain unique.

I also wanted my students to think about how dance can both tell stories and speak to empowering gender.

I framed my lesson around a loose history of dance, beginning at the oldest known form of dance and working my way forward. I told my students to focus on the dance, but to jot down any words that came to mind with each dance.

Bellydancing is agreed by most dance historians to be the oldest form of dance, having originated in Egypt at least 6000 years ago. It was thought to relate to the worship of honoring the female body which brought forth new life, which explains why its movements are generated from the torso, which is always exposed.

After the video, I asked my students to share the words that came to mind while watching the bellydancing, and wrote them on the board:

“Sexy. Flutter. Eye-catching. Red. Focused. Sparkle.”

The next-oldest form of dance is recognized to be Korean dance, which is thought to date back at least 5000 years. At its beginning, it was related to early shamanistic rituals, although it would come to be a practice specific to and sponsored by the Korean royal court. There was even a government ministry dedicated to its perpetuation and instruction.

After having my students watch the display of Korean dance, I paused my presentation and asked them to consider:

What is the same in these two dances?

“Both are wearing red. All the dancers are women. Both use bells. Both spin.

What is different?

“The belly dancer is alone. There is singing in the Korean dance. The Korean costumes are longer.

I next had my students look at a group of Indian dancers. Indian dance is about 4500 years old. Classical Indian dance was an integrated feature in Vedic rituals, which could either be done as part of ritual praise, or used much as ballet is in the Western tradition, to interpret canonical stories.

What is the same in all of the dances?

“Again, it’s all women. It seems to tell a story. The dance has props. Matching costumes.”

What is different?

“The dancers don’t always do the same steps. They are smiling. The dance is more athletic.

We moved from Indian to Japanese dance, the origins of which came from dancers in the royal courts of Korea and China 1300 years ago. There are at least six traditional genres of Japanese dance, from folk dancing which often related to food production (such as rice-farming and fishing) to the circular Noh dancing done in theatrical performances, to kabuki, a form of dance-drama.

This time, I asked my students to think about differences first.

What is different?

“It is very slow compared to other dances. She has a lot of makeup. The steps are very small. Her costume is tighter than the others.

What is the same?

“There is music. She is by herself, like the belly dancer. She has makeup that is like the Korean dancers.”

Following the ‘Dance of the Maiko’, I had my students look at ballet. Ballet is a type of performance dance that began in the Italian Renaissance courts of the 15th century and later developed into a concert dance form in France and Russia. It is the most highly technical form of dance, and is accompanied by classical music, often a full orchestra. Although ballet’s steps and famous ballets themselves (Swan Lake, Sleeping Beauty, etc.) have changed very little over time, a split in ballet practitioners in the mid-20th century led to modern dance as a separate discipline.

Again, I asked my students to think about what was different first:

“There is a man dancing with her. She dances on her toes. She is quite thin but so strong!”

What is the same?

“It tells a story. The dance is beautiful. They are graceful.”

I next had my students look at an example of Zulu dance. The Zulu represent the largest ethnic group in South Africa, but can also be found in Lesotho, Zimbabwe, Botswana, Malawi, and Mozambique. Traditionally, the Zulu are a warrior culture, and a number of their dances are ceremonial, and these can be related to events such as going to war or to celebrate a harvest. Genders are usually separate during dances. Dancing in the Zulu nation is thought to date back at least 400 years.

My students were very impressed by the contrast between ballet and the Zulu dance. If they had been a little less engaged with the ballet- which is, after all, a familiar form of dance- many sat up straighter in their chairs to see something so visibly different and striking.

Flipping back to my original questions, I asked: What is the same between Zulu dance, and the other dances that you have seen?

“Their movements are coordinated. They are in matching costumes, like the Korean dancers. They are performing.”

I then asked them to think about what was different when thinking about the dance:

“It is only men dancing. There is a lead dancer. They are dancing outside. There is some shouting.”

I then had my students look at an example of Irish dancing. Irish dance is at least 400 years old, although some dancing circles have been found in ancient places in Ireland, so it is likely older. The dancing practices of Ireland are closely associated with traditional Irish music. It is done in groups from 2 to 16 people, and was historically done on tabletops or even barrel tops.

I had my students again think about differences first:

“They do not use their arms very much. There are men and women, but not equal numbers. The musicians are on the stage with the dancers. Their shoes influence the steps and the music.”

And then I had them think about what was the same:

“They look serious. There is a main couple, like the ballet. They move together.”

We moved from Irish to Afro-Brazilian dance. Portuguese traders began bringing African slaves to Brazil around 1530, leading to the birth of a hybrid culture which is evident in dance, music, and art. Half of the Brazilian population today is of African ancestry. Afro-Brazilian dance evolved into a form with specific moves and steps by the late nineteenth century. One of the most well-known of these dances is called the samba, although Afro-Brazilian dance is often improvised.

What is the same between Afro-Brazilian and other dances?

“They are barefoot like the Zulu and the Indian dancers. They have musicians on-stage like the Irish and the Zulu dancers. They are wearing bright colors.”

What is different between Afro-Brazilian and other dances?

“Each dancer has a different role and costume. They wear dresses and pants. Their costumes are very big. Some of the dancers are singing.”

Last but not least, I presented one of the most modern forms of dance and the one that my students were most likely to be familiar with: hip-hop dance, which has been evolving since the 1970s. Though it is well-established in entertainment, it maintains a strong presence in urban neighborhoods and it has many forms. Like Afro-Brazilian dance, it is often improvisational in nature.

I think that my students were relieved to see a form of dance that they were expecting.

What is different between hip-hop and other forms of dance?

“It uses parts of different songs. It just looks cooler. I want to try it!”

What is the same between hip-hop and other forms of dance?

“They have a lot of energy. They move as a group. There are more women than men in the group.”